Is the Near Surface Disposal Facility (NSDF) at Chalk River Laboratories a Permanent Solution for Low-Level Radioactive Waste?

First Nation communities and citizens’ groups have launched court challenges against the proposed radioactive waste facility near the Ottawa River at Chalk River, citing environmental concerns and the potential hazards of the waste that will remain dangerous for thousands of years. The facility, intended to be built at the Chalk River Laboratories site in Deep River, Ontario, is designed to hold up to a million cubic meters of low-level radioactive waste. It has faced strong opposition from several First Nations, including the Kebaowek First Nation and Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg, who argue that the project was not adequately consulted with them and that it poses a threat to their traditional territories, cultural practices, wildlife, and the land.

Approval of the NSDF

On January 9, 2024, the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC) decided to amend the operating license for Canadian Nuclear Laboratories (CNL) at Chalk River Laboratories, allowing for the construction of a Near Surface Disposal Facility (NSDF) in Deep River, Ontario. This decision came after determining that, with proper mitigation and monitoring, the project would not likely have significant adverse environmental impacts. The area is on the unceded territory of the Algonquin Anishinaabeg. The Commission’s review, starting in 2016, affirmed the project’s robust design and safety, ensuring it could endure severe weather, seismic events, and climate change effects. The CNSC emphasized ongoing engagement with Indigenous Nations, including assessments and consultations to mitigate impacts on rights and the environment.

United in Opposition

Chiefs from First Nations, leaders from the Bloc Québécois, and the federal Green Party, along with concerned civil society organizations, have united to oppose this project, taking their fight to court. On February 14th, they rallied together on Parliament Hill to voice their united opposition. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau later clarified during a question period that the decision-making process was based on professional advice, not political motives.

About the Century-Long Project Plan

Purpose

The Near Surface Disposal Facility (NSDF) is designed for the secure containment and isolation of low-level radioactive waste. It is located 1.2 kilometers from the Ottawa River and covers an area of approximately 37 hectares. CNL has determined the site to be ideal owing to its natural geographical features, including a bedrock ridge that positions it well away from any flood zones, while also blending naturally with the surrounding forest landscape.

The Construction phase

The construction phase of the project is expected to last around three years, starting with initial site preparation activities such as clearing trees and setting up protective measures and buffer zones. The project is committed to reducing environmental impacts through efforts like engaging in sustainable forestry practices with Indigenous communities and implementing strategies to control dust, noise, and vibration from the outset.

At the heart of the NSDF’s design is the Engineered Containment Mound (ECM), which will occupy 17 hectares of the site. The construction approach for the ECM is phased, starting with initial works and the construction of the first six disposal cells, alongside essential infrastructure. A later phase, planned for 25 years after the start of operations, will add four more cells.

The design features include a perimeter berm built on stable bedrock, an advanced multi-layer baseliner system for managing leachate and protecting groundwater, and a cover system designed for environmental safety and waste isolation.

The operational and closure phase

Once construction is completed, the facility will move into an operational phase focused on the systematic receipt, sorting, and compaction of waste, all while adhering to strict safety and environmental protocols. This phase is expected to last 50 years, followed by a 30-year closure period that will focus on ongoing monitoring, maintenance, and preparation for an extended period of institutional control. In the period of closure, the emphasis shifts from the ongoing disposal of waste to extensive surveillance, upkeep, and arrangements for a minimum duration of 300 years under institutional governance.

(This information about the project comes from the official YouTube channel of Canadian Nuclear Laboratories.)

The current concern

Current apprehensions arise from the possibility that, before the planned cover is installed atop the mound, rainwater infiltration during the 50-year operational period could lead to the leaching of radioactive substances into the surrounding environment. To counteract this risk, the NSDF project has incorporated a wastewater treatment facility into its design, with the intention of discharging treated water either back into the groundwater system or directly into Perch Lake, which subsequently flows into the Ottawa River. The structure of the mound is engineered to endure for 550 years before it undergoes erosion, potentially releasing its contents into the natural environment.

But how long is this Low-level radioactive waste dangerous?

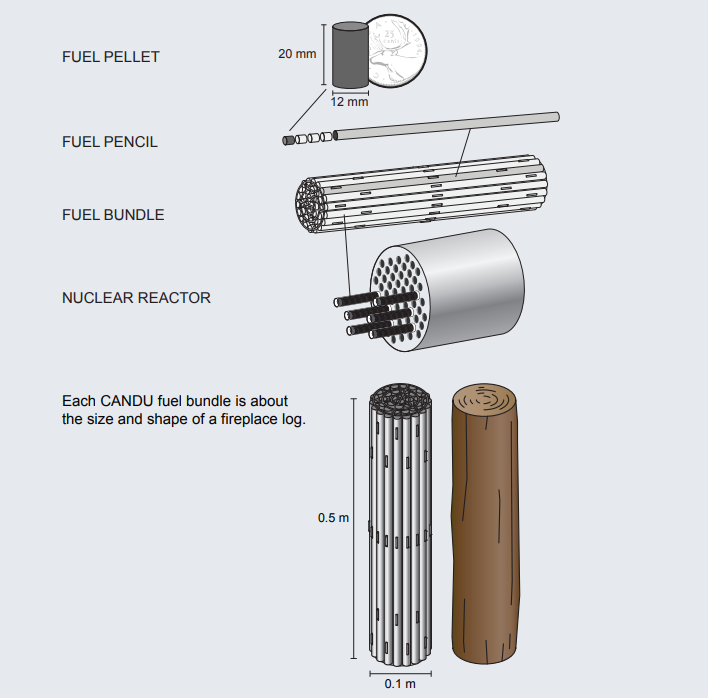

As of 2022, Canada’s existing inventory is about 3.2 million used nuclear fuel bundles. Now the used nuclear fuels are stored in seven interim facilities all over Canada. In Canada, the most used nuclear fuel that exists today is CANDU fuel.

This fuel is not a liquid or a gas — it is a stable solid. CANDU nuclear fuel consists of uranium dioxide (UO2 ) made from natural uranium. The ceramic pellets are placed inside a tube made of a zirconium-tin alloy, with the completed assembly called a fuel element or fuel pencil. These fuel pencils are welded together into bundles the shape and size of a fireplace log.

Longevity of Radioactivity

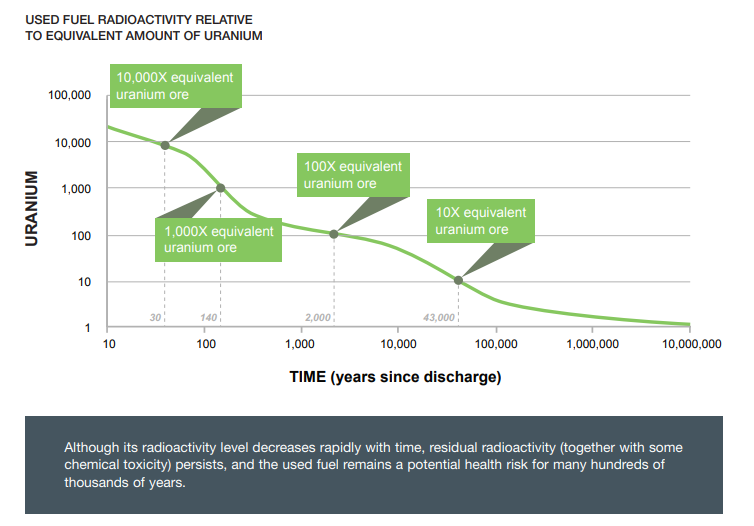

When CANDU fuel is removed from the reactor at the end of its useful life, it is considered a waste product. Used fuel is highly radioactive and requires careful management. Although its initial radioactivity level decreases rapidly with time, residual radioactivity (together with some chemical toxicity) persists, and the used fuel remains a potential health risk for a very long period of time. It will take about “one million years” for the radioactivity level to reach about that of an equivalent amount of natural uranium.

While low-level waste (LLW) accounts for about 90% of the total volume of radioactive waste, it only represents 1% of the total radioactivity, according to the World Nuclear Association. On the other hand, spent nuclear fuel, which contains radionuclides capable of emitting ionizing radiation such as gamma rays, neutrons, alpha, and beta particles, exhibits its highest level of radioactivity immediately after being removed from a reactor. According to the NWMO (Nuclear Waste Management Organization), this spent fuel continues to pose a significant hazard indefinitely. Given this context, the current plan, which anticipates a solution lasting up to 550 years, raises concerns about its permanency.

Considering that the individuals involved in these discussions will not be alive to witness the long-term outcomes, numerous questions and challenges regarding the sustainability and safety of this approach remain unresolved and groundwater pollution stands as a primary concern.

Points to Consider

Here are several key points to consider when evaluating the potential for groundwater pollution:

1. Proximity to the Ottawa River: The NSDF’s location, approximately 1.2 km away from the Ottawa River, raises concerns about the risk of contaminant migration into the river, impacting water quality and ecosystems. While the facility’s design includes measures to prevent environmental contamination, the long-term integrity of these measures is under scrutiny. A comprehensive and transparent water drainage analysis of the Ottawa River watershed, which encompasses regions within Ontario and Quebec, is to be conducted.

2. Engineered Containment Mound (ECM) Design: The ECM is designed to contain and isolate low-level radioactive waste, with multiple layers intended to prevent leachate (contaminated water) from seeping into the ground and reaching the groundwater. The effectiveness of this design in isolating radioactive materials over thousands of years, much beyond the mound’s designed lifespan of 550 years, is a central concern.

3. Waste Longevity vs. Mound Durability: Critics argue that the mound is designed to last only 550 years, while the radioactive waste it contains will remain hazardous for thousands of years. This discrepancy raises questions about the facility’s long-term effectiveness in isolating radioactive materials from the environment, including groundwater.

4. Leachate Management and Monitoring: The NSDF’s design includes a system for collecting and treating leachate. However, the effectiveness of this system in preventing any leachate from reaching groundwater, especially over long periods, is a concern. Continuous, effective monitoring and maintenance are essential to ensure its integrity.

5. Regulatory Oversight and Compliance: The Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC) has stated that the project is not likely to cause significant adverse effects if mitigation measures and monitoring are implemented. Yet, the citizens’ groups’ challenges and the subsequent judicial review indicate concerns about the adequacy of these measures and the rigour of regulatory oversight.

6. Cumulative Environmental Impacts: The potential cumulative impact of the NSDF, in conjunction with other projects at the same site, on groundwater quality is a concern. The interactions between different waste streams, containment measures, and natural processes need to be thoroughly understood and managed.

7. Mitigation Measures: Proposed mitigation measures, such as the controversial pipeline into Perch Lake, which critics argue could increase radioactive tritium flow into the Ottawa River, highlight the complexities of managing and mitigating potential environmental impacts, including on groundwater.

While the NSDF project includes extensive planning and engineering efforts aimed at preventing environmental contamination, the current concerns raised highlight significant uncertainties and potential risks, particularly regarding long-term groundwater protection.

The success of the NSDF in preventing groundwater pollution will largely depend on the long-term integrity and effectiveness of the containment measures, ongoing monitoring, and adaptive management strategies to address unforeseen issues.

The ongoing judicial review and public debate underscore the need for transparency, rigorous scientific evaluation, and community engagement in addressing these challenges.